Part I: Getting a PhD is hard, and you might not need one

My first two years of graduate school were disheartening; I was completely removed from youth- and education-related work. In my department, people often ask your “area of expertise.” If you do not have one, you are encouraged to find one. It felt disingenuous to answer that question when I had little work experience and most of my knowledge came from reading scholarly work. Other graduate students who struggle to find alignment between their work and research interests echo these sentiments; how can we claim competence in these content areas with such limited experience? I strongly oppose the position that obtaining a PhD makes you “an expert” in an area. Firstly, I think it’s impossible to achieve that status after five years, if at all. Secondly, only engaging with material related to one topic will not prepare me to work in cross-disciplinary, multi-sector, collaborative spaces.

After two years of misalignment between my graduate education and the experiences that motivate me, working to improve the lives of students, I asked myself, do I really need a PhD? In retrospect, I should have asked myself this question before applying to graduate programs. It was instilled in me as an undergraduate student that if I wanted to major in Psychology I would need to go to graduate school to get a job, and if I didn’t want to be a mental health counselor I would need a PhD. In the frenzy and excitement of the application process, I don’t think I ever sat down and did a simple job search to see if there were any positions that could offer me similar opportunities for growth and skill development. Although I have found my place now, I would encourage anyone considering graduate school to thoroughly deliberate whether a graduate degree is necessary and why they want one.

Part II: Getting a PhD is hard, and you might want one

During the spring of my second year here at MSU, I had the opportunity to join the Community-AID Lab and work on projects related to service integration in education systems. Being a part of Community-AID rejuvenated the passion that initially led me to apply to graduate school. I cannot emphasize enough how important it is for graduate students to explore opportunities with folks who share your values and substantive interests. I still, and always will, miss directly working with youth, but have found an environment that challenges and inspires me to be the best collaborator possible to those engaging in this important work.

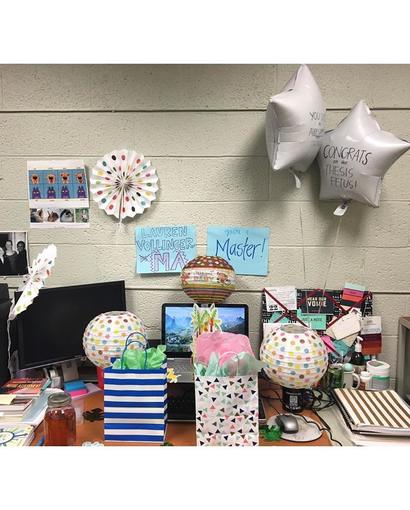

Although I am sometimes tempted to leave with my Masters and enter the workforce, I have embraced being here by understanding what purposes my graduate education does and does not serve for me. A PhD will not make me an expert of any kind, nor will it qualify me for every job I could dream of. A PhD will make me a better consumer and producer of knowledge and research. I see it as an opportunity to gain as many skills as possible and capitalize upon the resources available to me at a large research institution. My end goal is to support individuals doing amazing work to address adolescent inequities, and my graduate school experiences are preparing me to do this. A PhD probably isn’t necessary to accomplish my end goal, but it might position me to do better work.